(Approx 2 minute 40 second read)

I’m sure you have heard the term, ‘renshū’ (練習) – practice through repetition. It’s about ingraining a skill by doing it over and over again until it becomes second nature.

.

In many Western dojos, when a new technique, drill, or application is introduced, students will often carefully mimic the movement, and after a few attempts, they proclaim. “Got it!”.

.

But have they really?

.

This mindset reveals a key difference between Western and Japanese approaches to learning. Western students often believe that once they’ve grasped the surface mechanics of a movement, it’s time to move on to something new, which can feel more rewarding than the grind of repetitive practice.

.

In contrast, Japanese and Okinawan practitioners are taught from the beginning that true learning happens through doing. The same movement is repeated countless times until the body ‘feels’ the technique rather than simply knowing it. This highlights a distinction: learning by doing vs. simply knowing.

.

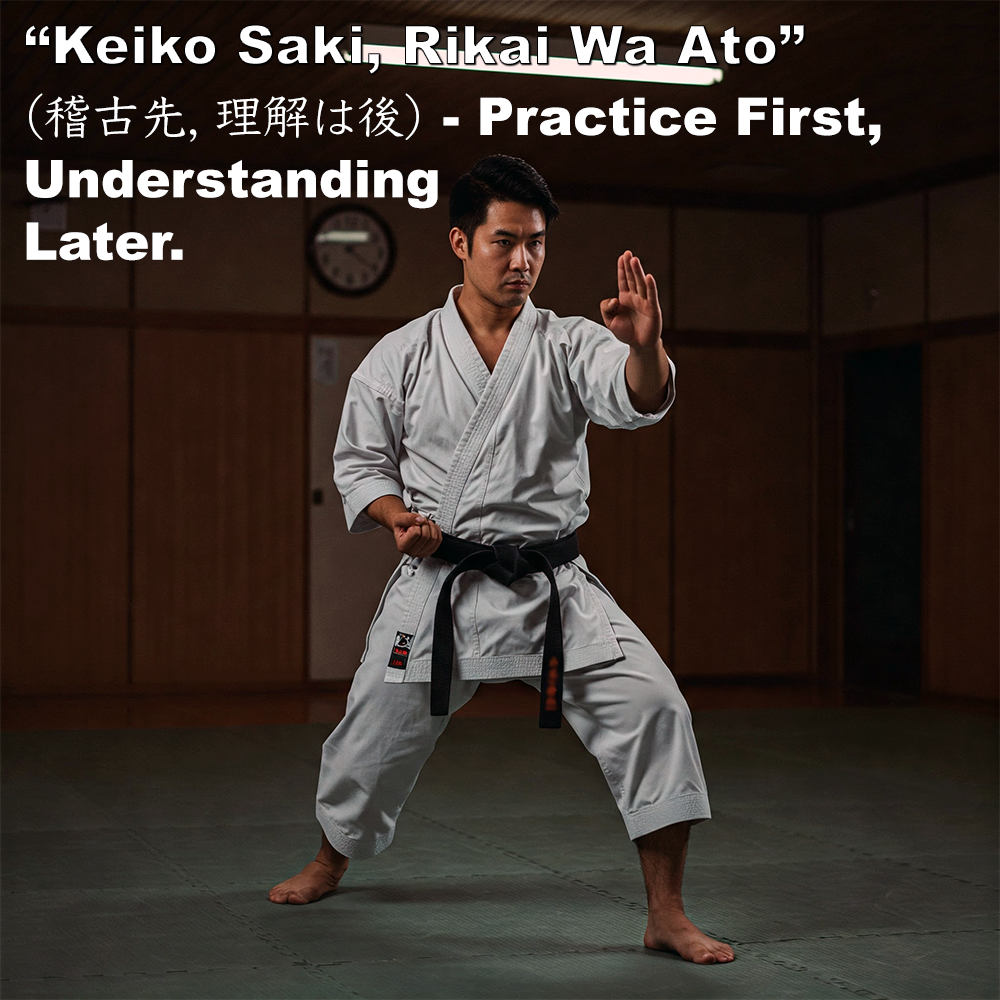

In Japan, the approach to learning is best summarized by the phrase “keiko saki, rikai wa ato” (稽古先, 理解は後) – practice first, understanding later. The expectation is that students trust the process and avoid excessive questioning. When a technique is taught, the immediate task is to train it, feel it, and internalize it through repetition.

.

Persistent questioning can come across as either impatience or a lack of respect for the teacher’s experience. One Japanese teacher once told me to simply “just train”. The message was clear: shut-up, stop asking, stop analyzing – just get on with it. The belief is that through repeated practice, the answers will eventually present themselves.

.

The Japanese approach is deeply kinesthetic. Through relentless repetition, students develop an intuitive understanding, the body learns through sensation, not intellectual analysis. A Japanese sensei might have students practice a single technique for many hours, before they move on to something else. This patient, disciplined practice is why the technical skill level in Japan often appears so refined.

.

Interestingly, this cultural mindset may explain why many of these practitioners don’t feel compelled to dissect kata to any great depth. From their perspective, the answers are already there, embedded in the movements.

.

For me the movement must be understood, not just performed.

.

The passive approach can often lead to simplistic, ineffective applications – primarily the familiar block-and-punch methods commonly seen today. The belief that the deeper lessons of kata will naturally reveal themselves has, in many cases, resulted in practitioners accepting surface-level bunkai applications. The result? A kata tradition that looks sharp in demonstrations but lacks practicality in real self-defense.

.

This is why, despite karate’s origins as a pragmatic self-protection system, so many practitioners train techniques that wouldn’t hold up under real pressure. Perhaps then, the cultural deference to repetition without inquiry has, in many cases, preserved the ‘form’ of karate while eroding its function.

.

Of course, there are exceptions – those who actively test, question, and explore applications beyond the block-and-punch formula. But in comparison to the broader karate populace, these individuals are few and far between.

.

In my opinion you should resist the urge to move on to something new the moment you think you’ve understood it. Don’t fall into the trap of mindless repetition, hoping that understanding will one day magically appear.

.

Train with intent. Question the application – after you’ve put in the work of course. Pressure-test your techniques.

.

True skill in karate doesn’t come from performing inch-perfect lines. It comes from true understanding, depth, context, and the willingness to go beyond the surface – one purposeful repetition at a time.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter