(Approx 2 minute 30 second read)

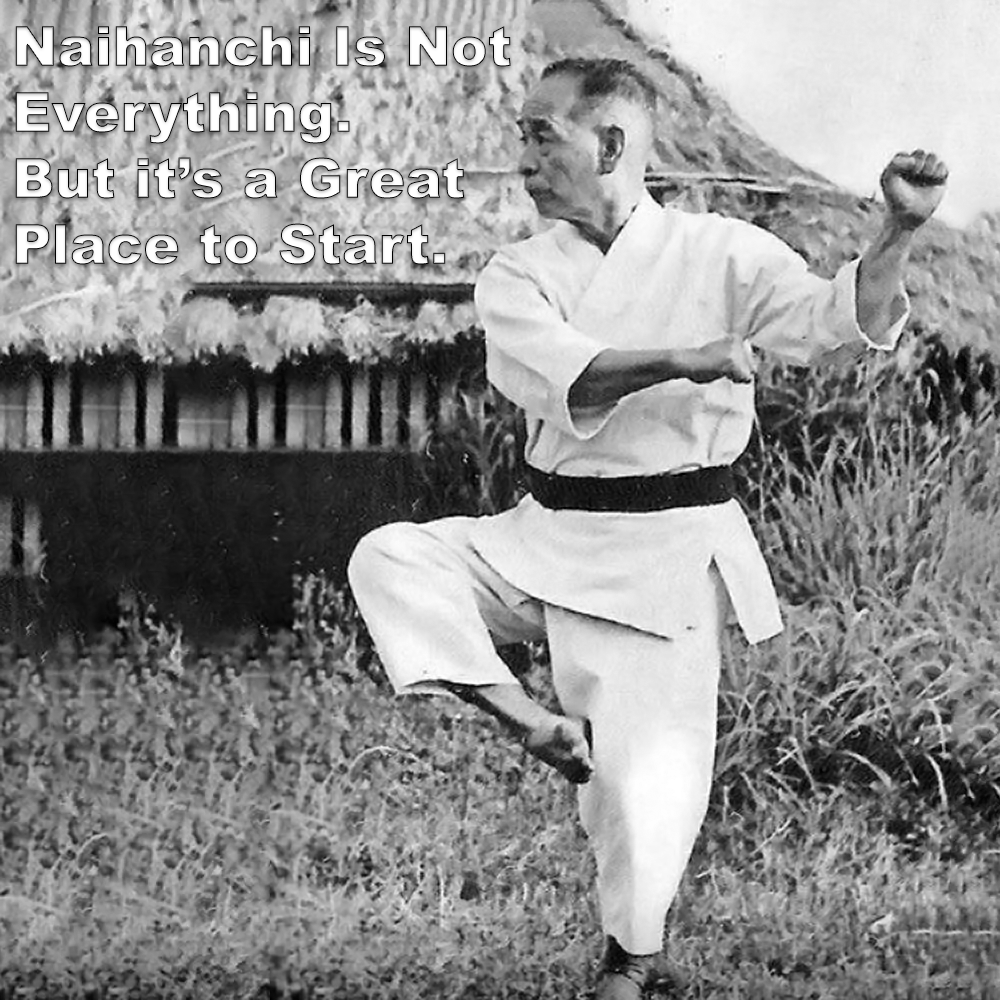

Naihanchi – one of my favourite kata.

.

Filled with close-range fighting and grappling techniques. It’s probable that Itosu believed Naihanchi to be so effective that, even if it was the only kata a student ever learnt, they would still become an able fighter.

.

The phrase “Everything is Naihanchi” came up on one of my articles. It was originally said in jest, but someone wanted to explore whether there was a deeper meaning behind it.

.

The idea was to consider, for a moment, that there might be some truth in the statement. His point wasn’t that Naihanchi specifically is everything, but that a single kata – any kata – could hold all the principles needed for understanding combat.

.

He suggested that each kata contains the same core principles, and that what sets them apart is simply the strategy behind how those principles are applied.

.

It’s an interesting view – but one that, in my opinion, leans toward oversimplification.

.

Kata can certainly be seen as complete systems. Each one presents its own structure – its own take on how to deal with violence. And deep study of a single kata can reveal a lot.

.

It is often said that the old masters would train one kata, like Naihanchi, for anywhere between three and ten years before learning another.

.

That kind of focused training was common in earlier times. But that doesn’t mean one kata is all you ever need.

.

Karate was never built on a single form. Its development involved many influences, teachers, and different ways of dealing with different problems – which is why we have so many different kata.

.

Each has its own flavour, addressing perhaps a singular problem, perhaps several – but never everything. That would simply be too much for one form.

.

Kata vary in approach. Some address grappling, others striking. Some control space differently. Each has its own tactical flavour. To say they’re all expressing the same thing misses the point.

.

Even Motobu Chōki – who is often closely associated with Naihanchi – didn’t limit himself to it alone. He said that each kata was a fighting system – not that one kata is the fighting system.

.

Yes, there are core ideas that run through kata. But it’s how they are shaped, applied, and adapted in each form that gives them meaning. It’s not just mechanics – it’s how tactics, positioning, and decision-making are layered into the structure. Seeing them all as the same is like saying every book with the same alphabet tells the same story.

.

At my dojo, we aim to understand how kata work – not just in isolation, but in relation to one another. We look for the core principles and common threads that run through them, recognising that while each kata has its unique expression, they contribute to a larger understanding.

.

We don’t pretend that all answers begin and end in one form. Karate is a system, not a shrine to a single shape.

.

No kata holds all the answers. Each one offers something. It’s the bigger picture that matters – and how we bring it to life in honest practice.

.

Of course, we don’t need to have twenty, thirty, or more kata. As Kenwa Mabuni, the founder of Shito-ryu, said: “If practiced properly, two or three kata will suffice as ‘your’ kata; all of the others can just be studied as sources of additional knowledge.” – (This is a notable statement, considering that Shito-ryu is known for its extensive syllabus – a testament to Mabuni’s dedication to preserving a wide range of kata.)

.

In the end, it’s not about choosing ‘the one’ kata – it’s about how well you understand and apply what’s inside them.

.

.

Written by Adam Carter